The Necessity of Intermediary Space

Architecture as the definition of boundaries

According to Dom Hans van der Laan, architecture is a necessary material completion of nature. Unlike all other living creatures, which are fully integrated into the homogeneous order of nature, humans are rebelling against nature. In order to overcome this conflict we are making artefacts. Every artefact, including architecture, is an intermediary between man and his natural environment, which bears the characteristics of both and thus has the ability to reconcile them. (Padovan, 1989, p. 23-24) To explain this intermediary role of architecture he compares the house we inhabit with a sandal we wear on our feet. “The ground is too hard for our bare feet, therefor we wear sandals, with soles of softer material than the ground, but stronger than our feet. (…) The top of the sole represents a piece of soft ground for the foot, while the bottom of the sole opposite to the ground plays the role of a hard foot. Likewise, the house is a habitable environment for humans on the inside, while on the outside, where it is confronted with nature, it means an inviolable human existence.” (Laan, 1977, p. 1-2)

The architecture of van der Laan is fundamentally concerned with the idea of boundaries. According to van der Laan people have the necessity to define boundaries within the infinite natural environment, so that we can relate ourselves to it. “Architecture arises when we add solid, vertical walls to the horizontal surface of the earth.” (Padovan, 1989, p. 24) Van der Laan calls the space that is limited by the walls our ‘experience space’. This ‘experience space’ however, is not homogeneous. It has a more intimate zone of action and a larger zone of walking. All of these movements are led by our senses, especially through our eyes. Thus the ‘experience space’ is a superposition of growing spaces: a space of action (the ‘cella’), a walking space (the ‘court’) and a field of view (the ‘domain’). Therefore, the ‘experience space’ should consist of three successive types of demarcation. (Laan, 1977, p. 28)

Before I was familiar with the work of Dom Hans van der Laan, I did not look at architecture from this viewpoint so explicitly. Whereas the modernists saw the elimination of the separation between inside and outside as the great conquest of the new architecture, van der Laan sees the polarity of inside and outside space as an essential architectural phenomenon. I think it is a very interesting perspective on architecture and therefore I would like to bring forward some different positions on this subject. What do other architects think about architecture as a means to create boundaries? How can we define boundaries in architecture? And why do we need them? The oeuvre of van der Laan shows some similarities with the work of Louis Kahn. Both architects were searching for the essence of space. Both architects were fascinated with historical buildings and ruins. And both architects share the idea of architecture as the definition of boundaries. According to Kahn, architecture meant nothing less than the exercise of human will to apply clear boundaries to the nebulous space surrounding us. The boundaries that are imposed create a room. And this, Kahn believed, is the beginning of architecture. (Saito, 2003, p. 31) This notion of the room is quite similar to the notion of the ‘experience space’ or the ‘cella’ of van der Laan. Nevertheless Kahn brings in another notion, that of the intermediate area: a semi-outdoor space that is neither inside nor outside. The portico of the Kimbell Art Museum is the most refined example. (Saito, 2003, p. 13) We do not see this kind of notion in the oeuvre of van der Laan.

Herman Hertzberger is an architect that elaborated extensively on the notion of the intermediate area. In his view intermediate spaces, such as porches, canopies, balconies, loggias, terraces and sidewalks help to soften harsh and abrupt boundaries between inside and outside and will allow an accommodation between adjacent worlds. (Hertzberger, 1996, p. 86). He calls this intermediate space a spatial ‘threshold’.

He illustrates the value of this notion with the example of a child sitting on the sidewalk in front of his house. The child is far enough removed from his mother to feel independent, having the excitement and adventure of the unknown. However, the child feels close enough to his mother to feel safe, because the sidewalk does not only belong to the street but also to the house. The child is situated inside and outside simultaneously. This ambiguity exists because of the intermediate quality of the sidewalk, a place where two worlds meet and a space in itself, instead of a sharply drawn boundary. (Hertzberger, 1996, p. 32)

Christopher Alexander categorised various transitions between inside and outside, public and private and tried to examine architectural means to order these different conditions. In his book ‘A Pattern Language’ he states that “there is too little ambiguity between indoors and outdoors.” (Alexander, 1977, p. 562) He elaborates on the reason why people need spatial thresholds: According to Alexander, a physical transition space, creates a transition in your mind and behaviour as well. He explains this by the argument that people fulfil different roles in different spaces. People cannot adapt to another role unless there is a physical transition. “The experience of entering a building influences the way you feel inside the building. If the transition is too abrupt there is no feeling of arrival, and the inside of the building fails to be an inner sanctum.” (Alexander, 1977, p. 549) To illustrate how these transitions can be defined by architectural means he gives four examples of entrance transitions to a house. Each one of them creates the physical transition with a different combination of architectural elements. I one case there is a kind of entry court behind the front door, in another case, the transition is formed by a curve in the path that takes you through a gate on the way to the front door. “In all cases, what matters most is that the transition exists, as an actual physical place.” (Alexander, 1977, p. 551)

From the outside space to the most intimate space within the home, there are various and culturally dependent boundaries, transitions and thresholds. Birgit Jurgenhake and Kisho Kurokawa researched the transitions between outside and inside and between public and private in Japanese architecture.

Kurokawa explains that the difference between Western and Japanese space is that “the former is discrete and the latter is continuous. Western architecture is designed to ‘conquer’ nature, thus the significance of the wall, dividing exterior from interior. Japanese space, by contrast, seeks to encompass building and nature, to unite them as equal partners. The wall as divider between outside and inside did not evolve in Japan, (…) because of a difference in basic materials: Japan is a culture of wood and the West a culture of stone or brick. In addition, Japanese builders have long made a conscious effort to integrate inside and outside.” (Kurokawa, 1997, Chapter 9)

To illustrate the difference between Western and Japanese space, both Kurokawa and Jurgenhake describe architectural elements of the traditional Japanese house, the Machiya. Living in a Machiya means that you undergo life in a dwelling condition of ambiguity. The borders between the inside and outside, public and private are quite vague. As you move from one space to the other a world of transitions and ambiguous spaces will occur. You are inside and outside at the same moment.

The best example of an intermediary space is the engawa, which is both part of the outside and the inside. “The engawa is a sort of veranda running around the house as a projecting platform on stilts and protected by the eaves. It serves as an exterior corridor, mediating between inside and outside.” (Kurokawa, 1997, Chapter 9)

Researching different positions on the subject of architecture as a means to create boundaries actually let me to the conclusion that the space between the boundaries is more important than the boundaries themselves. Although the definition of boundaries lies at the core of architecture as van der Laan suggests, defining the intermediary spaces is of even more importance.

References

Aben, R., Wit, S. d., & Jong, S. d. (1998). De omsloten tuin: Geschiedenis en ontwikkeling van de hor tus conclusus en de herintroductie ervan in het hedendaagse stadslandschap. Rotterdam: Uitgeverij 010.

Alexander,C.,Ishikawa,S.,& Silverstein,M.(1977).A pattern language: Towns,buildings,construction. New York: Oxford University Press.

Hertzberger, H. (1996). Ruimte maken, ruimte laten: Lessen in architectuur. Rotterdam: 010.

Jurgenhake, B. (2011).The qualities of the Machiya: An architectural research of a traditional house in Japan.

Kurokawa, K. (1997). Each one a hero:The philosophy of symbiosis.Tokyo: Kodansha.

Laan, H. v. d. (1977). De architectonische ruimte:Vijftien lessen over de dispositie van het menselijk verblijf. Leiden: Brill.

Padovan, R., & Crouzen, B. (1989). Dom Hans van der Laan, architecture and the necessity of limits. Maastricht: Stichting Manutius.

Saito,Y. (2003). Louis I. Kahn houses: 1940-1974. Tokyo:TOTO Shuppan.

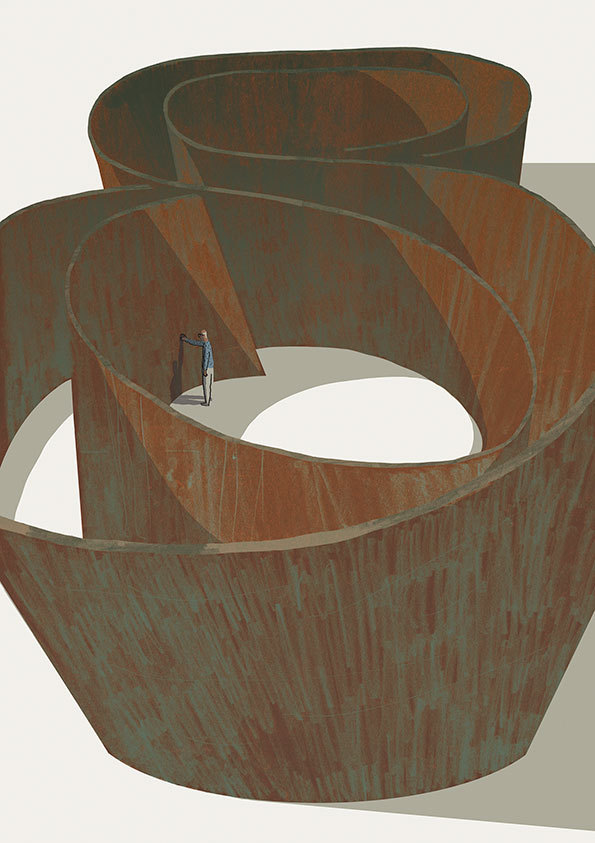

Image: Josh Cochran: Serra

The architecture of van der Laan is fundamentally concerned with the idea of boundaries. According to van der Laan people have the necessity to define boundaries within the infinite natural environment, so that we can relate ourselves to it. “Architecture arises when we add solid, vertical walls to the horizontal surface of the earth.” (Padovan, 1989, p. 24) Van der Laan calls the space that is limited by the walls our ‘experience space’. This ‘experience space’ however, is not homogeneous. It has a more intimate zone of action and a larger zone of walking. All of these movements are led by our senses, especially through our eyes. Thus the ‘experience space’ is a superposition of growing spaces: a space of action (the ‘cella’), a walking space (the ‘court’) and a field of view (the ‘domain’). Therefore, the ‘experience space’ should consist of three successive types of demarcation. (Laan, 1977, p. 28)

Before I was familiar with the work of Dom Hans van der Laan, I did not look at architecture from this viewpoint so explicitly. Whereas the modernists saw the elimination of the separation between inside and outside as the great conquest of the new architecture, van der Laan sees the polarity of inside and outside space as an essential architectural phenomenon. I think it is a very interesting perspective on architecture and therefore I would like to bring forward some different positions on this subject. What do other architects think about architecture as a means to create boundaries? How can we define boundaries in architecture? And why do we need them? The oeuvre of van der Laan shows some similarities with the work of Louis Kahn. Both architects were searching for the essence of space. Both architects were fascinated with historical buildings and ruins. And both architects share the idea of architecture as the definition of boundaries. According to Kahn, architecture meant nothing less than the exercise of human will to apply clear boundaries to the nebulous space surrounding us. The boundaries that are imposed create a room. And this, Kahn believed, is the beginning of architecture. (Saito, 2003, p. 31) This notion of the room is quite similar to the notion of the ‘experience space’ or the ‘cella’ of van der Laan. Nevertheless Kahn brings in another notion, that of the intermediate area: a semi-outdoor space that is neither inside nor outside. The portico of the Kimbell Art Museum is the most refined example. (Saito, 2003, p. 13) We do not see this kind of notion in the oeuvre of van der Laan.

Herman Hertzberger is an architect that elaborated extensively on the notion of the intermediate area. In his view intermediate spaces, such as porches, canopies, balconies, loggias, terraces and sidewalks help to soften harsh and abrupt boundaries between inside and outside and will allow an accommodation between adjacent worlds. (Hertzberger, 1996, p. 86). He calls this intermediate space a spatial ‘threshold’.

He illustrates the value of this notion with the example of a child sitting on the sidewalk in front of his house. The child is far enough removed from his mother to feel independent, having the excitement and adventure of the unknown. However, the child feels close enough to his mother to feel safe, because the sidewalk does not only belong to the street but also to the house. The child is situated inside and outside simultaneously. This ambiguity exists because of the intermediate quality of the sidewalk, a place where two worlds meet and a space in itself, instead of a sharply drawn boundary. (Hertzberger, 1996, p. 32)

Christopher Alexander categorised various transitions between inside and outside, public and private and tried to examine architectural means to order these different conditions. In his book ‘A Pattern Language’ he states that “there is too little ambiguity between indoors and outdoors.” (Alexander, 1977, p. 562) He elaborates on the reason why people need spatial thresholds: According to Alexander, a physical transition space, creates a transition in your mind and behaviour as well. He explains this by the argument that people fulfil different roles in different spaces. People cannot adapt to another role unless there is a physical transition. “The experience of entering a building influences the way you feel inside the building. If the transition is too abrupt there is no feeling of arrival, and the inside of the building fails to be an inner sanctum.” (Alexander, 1977, p. 549) To illustrate how these transitions can be defined by architectural means he gives four examples of entrance transitions to a house. Each one of them creates the physical transition with a different combination of architectural elements. I one case there is a kind of entry court behind the front door, in another case, the transition is formed by a curve in the path that takes you through a gate on the way to the front door. “In all cases, what matters most is that the transition exists, as an actual physical place.” (Alexander, 1977, p. 551)

From the outside space to the most intimate space within the home, there are various and culturally dependent boundaries, transitions and thresholds. Birgit Jurgenhake and Kisho Kurokawa researched the transitions between outside and inside and between public and private in Japanese architecture.

Kurokawa explains that the difference between Western and Japanese space is that “the former is discrete and the latter is continuous. Western architecture is designed to ‘conquer’ nature, thus the significance of the wall, dividing exterior from interior. Japanese space, by contrast, seeks to encompass building and nature, to unite them as equal partners. The wall as divider between outside and inside did not evolve in Japan, (…) because of a difference in basic materials: Japan is a culture of wood and the West a culture of stone or brick. In addition, Japanese builders have long made a conscious effort to integrate inside and outside.” (Kurokawa, 1997, Chapter 9)

To illustrate the difference between Western and Japanese space, both Kurokawa and Jurgenhake describe architectural elements of the traditional Japanese house, the Machiya. Living in a Machiya means that you undergo life in a dwelling condition of ambiguity. The borders between the inside and outside, public and private are quite vague. As you move from one space to the other a world of transitions and ambiguous spaces will occur. You are inside and outside at the same moment.

The best example of an intermediary space is the engawa, which is both part of the outside and the inside. “The engawa is a sort of veranda running around the house as a projecting platform on stilts and protected by the eaves. It serves as an exterior corridor, mediating between inside and outside.” (Kurokawa, 1997, Chapter 9)

Researching different positions on the subject of architecture as a means to create boundaries actually let me to the conclusion that the space between the boundaries is more important than the boundaries themselves. Although the definition of boundaries lies at the core of architecture as van der Laan suggests, defining the intermediary spaces is of even more importance.

References

Aben, R., Wit, S. d., & Jong, S. d. (1998). De omsloten tuin: Geschiedenis en ontwikkeling van de hor tus conclusus en de herintroductie ervan in het hedendaagse stadslandschap. Rotterdam: Uitgeverij 010.

Alexander,C.,Ishikawa,S.,& Silverstein,M.(1977).A pattern language: Towns,buildings,construction. New York: Oxford University Press.

Hertzberger, H. (1996). Ruimte maken, ruimte laten: Lessen in architectuur. Rotterdam: 010.

Jurgenhake, B. (2011).The qualities of the Machiya: An architectural research of a traditional house in Japan.

Kurokawa, K. (1997). Each one a hero:The philosophy of symbiosis.Tokyo: Kodansha.

Laan, H. v. d. (1977). De architectonische ruimte:Vijftien lessen over de dispositie van het menselijk verblijf. Leiden: Brill.

Padovan, R., & Crouzen, B. (1989). Dom Hans van der Laan, architecture and the necessity of limits. Maastricht: Stichting Manutius.

Saito,Y. (2003). Louis I. Kahn houses: 1940-1974. Tokyo:TOTO Shuppan.

Image: Josh Cochran: Serra

"Nature has three different aspects which we cannot comprehend: it is unlimited, without form and without measure. Architecture is nothing else but an addition to the natural space to make it habitable. That is: limited in relation to our bodies, visible to our senses and measurable for our intellect."

Dom Hans van der Laan, 1985

speaking to his architecture students

(Padovan, 1989, p. 24)